The lead-up to the 2018 midterm elections has seen a record number of women win primaries for the Democratic Party. Not only is the party fielding more women candidates than ever before, women are more likely to vote for Democrats than men. In new research Heather L. Ondercin investigates this gender gap in partisanship, finding that it began to develop in the 1960s, rather than in the 1980s as many had previously thought. What has characterized this gender gap, she writes, is that as the gender imbalance between who both parties elect has grown, so has their support from men and women, with women increasingly favoring Democrats and men, Republicans.

The lead-up to the 2018 midterm elections has seen a record number of women win primaries for the Democratic Party. Not only is the party fielding more women candidates than ever before, women are more likely to vote for Democrats than men. In new research Heather L. Ondercin investigates this gender gap in partisanship, finding that it began to develop in the 1960s, rather than in the 1980s as many had previously thought. What has characterized this gender gap, she writes, is that as the gender imbalance between who both parties elect has grown, so has their support from men and women, with women increasingly favoring Democrats and men, Republicans.

The midterm elections in the United States are fast approaching. In the frenzied lead-up pundits and pollsters are focusing on the role that women are playing. A record number are running for elected office and have been relatively successful in the primaries. Surveys over the past several months estimate that women voters are 8 to 13 points more likely to vote for the Democratic candidate than men voters.

My research on the gender gap in partisanship (where women are more likely to vote for Democrats than men) provides critical insights into how gender will shape the outcome of the 2018 and future elections. In new research I answer three critical questions about the gender gap in partisanship: when did it emerge, what influences its growth, and who is responsible for it. Understanding the gender gap in partisanship is essential because partisanship is such a dominant force in US politics, shaping how American vote and interpret the political world.

When did the gender gap emerge?

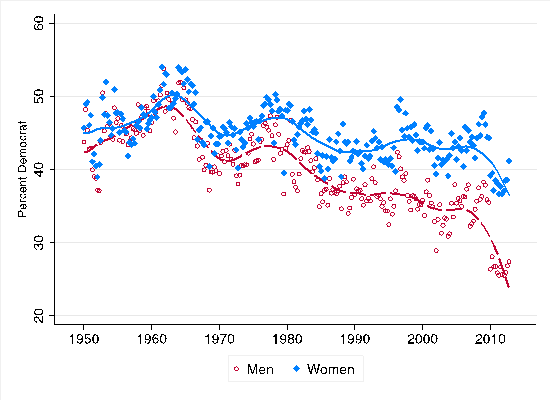

My research shows that the gender gap in partisanship emerged much early than what is commonly thought. The 1980 Presidential election is frequently identified as the beginning the gender gaps in US politics, as then women were 8 percent less likely to vote for Ronald Reagan than men. Figure 1 shows that differences in partisanship actually developed in the late 1960s and have continued to grow over time. During the 1970s, the difference between men’s and women’s party identification grew by about a point, averaging 3.4 percent. The gap has continued to widen each subsequent decade, averaging 5.2 percent in the 1980s, 6.8 percent in the 1990s, 8.5 percent in the 2000s, and 11.7 percent between 2010 and 2012. During these later decades, the growth in the gap appears to be caused by increasing women’s Democratic Partisanship and decreasing men’s Democratic partisanship.

Figure 1 – Emerging gender gap in Democratic voters

What influences the growth of the gender gap?

My research identifies changes in the composition of party elites which voters use as cues about the representation of different groups by the parties, as driving the gender gap. When these cues change, we would expect to see voters respond. Two significant transformations occurring in the parties over the past 60 years have been related to gender and race.

First, during the 1950s women were elected to both parties in equal numbers, but over time, women have come to represent a larger portion of the Democratic Party’s congressional delegation than in the Republican Party’s. When looking towards the parties for a cue regarding the representation of gender the lopsided presence of women among political elites sent a clear message about the parties.

Second, Southern realignment reshaped the composition of congressional delegations. In response to changes in the racial policy positions of the Democratic Party, the congressional delegations sent from Southern states slowly transitioned from being solidly Democratic to being dominated by Republicans. This process aligned minorities with the Democratic Party in the minds of voters. I argue that voters used this cue about how the parties represent politically marginalized groups, including women.

Image credit: We the people by Alice Donovan Rouse from Unsplash

Who is responsible for the gender gap?

In the 1980s the gender gap was initially thought to be a result the second wave of the US women’s movement empowering women voters. Shortly after that, though many noticed that men were moving away from the Democratic Party. So we see that both men and women caused the formation and evolution of the gender gap.

Women and men voters responded differently to the signals sent by the parties regarding the representation of groups. In response to the gender imbalance between the Democratic and Republican parties, men and women moved in opposite directions. Women increased and men decreased their Democratic Partisanship. Both men and women left the Democratic Party as a result of Southern realignment. After 1980, Southern realignment became less important for women, while men continued to decrease their Democratic partisanship in response.

What does this mean for 2018 midterms and future elections?

The increased differences between men’s and women’s partisan attachments suggest that the gender gap in vote choice will continue to grow. Partisanship is the most important factor shaping how people vote. Since women are more likely to identify with the Democratic Party, we would expect that they will also vote for Democratic candidates. But not all women are Democrats, and women who identify as Republican are unlikely to vote for the opposite party’s candidate. The magnitude of the gender gap in the 2018 and other elections will depend on how well the Democratic Party is able to mobilize voters compared to the Republican Party’s ability to mobilize voters.

The growth in the gender gap should not be interpreted as men and women being on opposing sides of the political spectrum. While gender is an important political identity, there are other identities, such as race and class, which shape the partisan attachments of both men and women.

The 2018 primary election may have long-term consequences for the gender gap. A record number of women are running for elected office this year. Moreover, most of those women are Democratic women. The outcome and media attention devoted to Democratic women candidates will help reinforce the image individuals have in their heads regarding gender representation and the parties. As a result, we would expect this election to strengthen existing partisan connections and shape partisan attachments.

- “Who Is Responsible for the Gender Gap? The Dynamics of Men’s and Women’s Democratic Macropartisanship, 1950–2012” in Political Research Quarterly

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2wlInRj

About the author

Heather L. Ondercin – Wichita State University

Heather L. Ondercin – Wichita State University

Heather L. Ondercin is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Wichita State University. She researches how gender shapes political behavior over time in the United States. Her work has been published in outlets including Political Research Quarterly, Political Behavior, and Electoral Studies. She is working on a book project titled Politicized Identities and the Partisan Gender Gap.